George R. Lawrence Transformed Photography With Kites And Explosions

by Ivan Farkas

An underappreciated innovator in the world of photography, George R. Lawrence’s love of visually recording a single moment in time —enlivened by his many brushes with death — led to revolutionary contributions to the art form.

Lawrence originally worked as a carriageer— or, as everyone other than me calls the profession, wainwright— at a wagon factory in Chicago in 1889. Shortly thereafter, he and a partner, Irwin W. Powell, opened a studio that dealt in “crayon enlargements” — a version of photo-crayotype which is, more or less, hand-coloring a black and white photo.

In 1893, however, Powell left the studio, presumably after a series of escalating comedic ‘80s-sitcom-worthy spats, like drawing a line down the middle of the studio and eating each other’s leftovers. Regardless of reasons, Lawrence found he had inherited a bunch of nice equipment and, armed with newfound knowledge he had gained from a photographer friend, he decided to start the Geo. R. Lawrence Company, asserting: “The Hitherto Impossible in Photography is Our Specialty.”

And it definitely was, as was apparent when he designed and built the largest camera in the world, after being commissioned to take a picture of some fancy-pants train. The Chicago & Alton Railway’s masterpiece, The Alton Limited, was an enormous, extravagant locomotive with luxurious, perfectly symmetrical cars that were all splendiferous in every way. It was also known as “the handsomest train in the world,” because the phrase “check out our sexy new longboi” and the heart-eyes emoji hadn’t been invented yet.

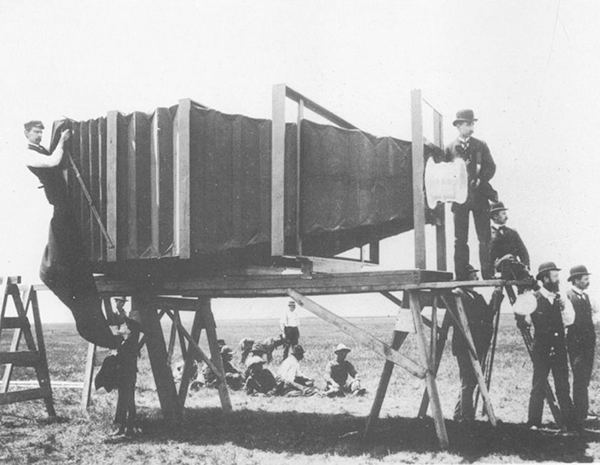

So Lawrence developed the Mammoth Camera, a 1,400 pound beast that cost $5,000 ($170,000 today) to build, and had a bellows so large you could crawl inside. Sadly, there are no surviving pictures of this fantastic device and— HAHA! Just kidding, there totally are, and this thing is bitchin’:

And it took all of these people to operate the damn thing.

The resulting photograph was eight feet long and required ten gallons of chemicals to process. And after dealing with some brief allegations of fakery, Lawrence ended up receiving the Grand Prize of the World for Photographic Excellence in 1900, which I assume came with a Certificate of Achievement, a sandwich voucher (limit: one), and a hearty handshake.

Lawrence is also the father of flash photography, known as “Flashlight Lawrence,” because of his propensity for messing about with magnesium flares, which would then blow up in his face, while rupturing his eardrums and vaporizing his hair, eyebrows, and whiskers. But at least this led to a method he devised for taking group photos, by simultaneously combusting as many as 350 separate flash charges placed around a room.

Believe it or not, snagging this shot was not an easy feat at the time.

Not content with trying to explode his own face off, Lawrence later became the first commercial photographer to dabble in badass aeronautics. His courtship with that forbidden domain, air, began by flirting with modest elevations. He snapped pics from ladders, built his own telescoping towers, and probably practiced a fair amount while standing up on his tippy-toes, real tall. Unfortunately, these methods did not produce the results he was looking for, so instead he simply ... built a vehicle. Specifically, a platform attached to the bottom of an anchored balloon.

Of course, the flimsy thing unexpectedly (predictably?) detached one day, and Lawrence fell 230 feet before telephone and telegraph wires saved his life, much in the same way they’ve saved many a cartoon character’s ass over the years. And while Lawrence didn’t completely abandon the idea of balloons, he was more intrigued by the idea of a kite-based solution, so he started stringing a bunch of kites together that could lift a panoramic camera, whose shutter release was triggered by a small electric current sent up via a long, connected wire.

Thusly, in 1906 he photographed the ruins of San Francisco, in the wake of the city’s historic earthquake, from the lofty perch of 2,000 feet o’er the bay.

He sold the prints for $125 a pop, made a slick $15,000, then traveled to Africa to photograph the wilds. Afterward, he left the photo biz and began inventing aircraft, including winged zeppelins. But since I don’t recall any stories from history about an F-800 Lawrence Wing downing some Nazi aircraft, I’d say that Lawrence is rightly remembered more for his contributions to photography than he is for aeronautical design. Well, except for when that aircraft was being designed to haul a camera.